жңҖж–°гҒ®иЁҳдәӢ

гғ–гғӘгғӮгӮ№гғҲгғізҫҺиЎ“йӨЁгҒҢгӮ«гӮӨгғҰгғңгғғгғҲгҒ®гҖҠгӮӨгӮЁгғјгғ«гҒ®е№іеҺҹгҖӢгӮ’ж–°жүҖи”өпјҶеұ•зӨә

гғ–гғӘгғӮгӮ№гғҲгғізҫҺиЎ“йӨЁгҒҢгӮ«гӮӨгғҰгғңгғғгғҲгҒ®гҖҠгӮӨгӮЁгғјгғ«гҒ®е№іеҺҹгҖӢгӮ’ж–°жүҖи”өпјҶеұ•зӨә

гғ©гғігғҖгғ иЎЁзӨә

- 2015е№ҙ2жңҲ (2)

- 2014е№ҙ12жңҲ (4)

- 2014е№ҙ11жңҲ (2)

- 2014е№ҙ5жңҲ (2)

- 2014е№ҙ3жңҲ (1)

- 2013е№ҙ12жңҲ (3)

- 2013е№ҙ11жңҲ (1)

- 2013е№ҙ10жңҲ (1)

- 2013е№ҙ8жңҲ (2)

- 2013е№ҙ3жңҲ (3)

- 2013е№ҙ2жңҲ (2)

- 2013е№ҙ1жңҲ (3)

- 2012е№ҙ9жңҲ (3)

- 2012е№ҙ4жңҲ (1)

- 2012е№ҙ2жңҲ (2)

- 2011е№ҙ10жңҲ (4)

- 2011е№ҙ9жңҲ (5)

- 2011е№ҙ8жңҲ (5)

- 2011е№ҙ7жңҲ (8)

- 2011е№ҙ4жңҲ (2)

- 2011е№ҙ2жңҲ (1)

- 2010е№ҙ12жңҲ (2)

- 2010е№ҙ10жңҲ (3)

- 2010е№ҙ9жңҲ (4)

- 2010е№ҙ8жңҲ (2)

- 2010е№ҙ7жңҲ (5)

- 2010е№ҙ6жңҲ (6)

- 2009е№ҙ11жңҲ (1)

- 2009е№ҙ6жңҲ (30)

- 2009е№ҙ3жңҲ (1)

- 2009е№ҙ2жңҲ (4)

- 2009е№ҙ1жңҲ (6)

- 2008е№ҙ12жңҲ (6)

- 2008е№ҙ11жңҲ (6)

- 2008е№ҙ10жңҲ (12)

- 2008е№ҙ9жңҲ (1)

- 2008е№ҙ7жңҲ (1)

- 2008е№ҙ6жңҲ (11)

- 2008е№ҙ5жңҲ (3)

- 2008е№ҙ3жңҲ (9)

- 2008е№ҙ2жңҲ (2)

- 2008е№ҙ1жңҲ (8)

- 2007е№ҙ12жңҲ (1)

- 2007е№ҙ11жңҲ (4)

- 2007е№ҙ9жңҲ (9)

гӮөгӮ¶гғ“гғјгӮәгҒ®гҖҢгғўгғігӮҪгғје…¬ең’гҖҚиЁі

д»ҘеүҚгҒ«гӮҜгғӘгӮ№гғҶгӮЈгғјгӮәгҒ§еЈІгӮҠгҒ«еҮәгҒ•гӮҢгҒҰгҒ„гҒҹгҖҢзүЎи ЈгҒ®йқҷзү©з”»гҖҚгҒ«гҒӨгҒ„гҒҰгҒ®зҝ»иЁігӮ’гҒҠеұҠгҒ‘гҒ—гҒҫгҒ—гҒҹгҒҢ

е…Ҳж—ҘгӮөгӮ¶гғ“гғјгӮәгҒ§гӮӮгҖҢгғўгғігӮҪгғје…¬ең’гҖҚгҒ®гӮӘгғјгӮҜгӮ·гғ§гғігҒҢгҒӮгҒЈгҒҹгӮҲгҒҶгҒӘгҒ®гҒ§гҒҫгҒҹзҝ»иЁігҒ—гҒҰгҒҝгҒҫгҒ—гҒҹгҖӮ

йҒҺеҺ»гҒ«еҸ–гӮҠжүұгӮҸгӮҢгҒҹдҪңе“ҒгӮӮгҒқгӮҢгҒӘгӮҠгҒ«гҒӮгӮӢгҒ—гҖҒгҒҫгҒҹиӘӯгӮ“гҒ§гҒҝгҒӘгҒҸгҒЈгҒЎгӮғпјҒпјҒ

гӮөгӮ¶гғ“гғјгӮәгҒ®е…ғгғҡгғјгӮёгҒҜгҒ“гҒЎгӮү >>

зҝ»иЁідёӯгҒ®гҖҢеӣігҖҚгҒ«гҒӨгҒ„гҒҰгҒҜе…ғгғҡгғјгӮёгӮ’гҒ”иҰ§дёӢгҒ•гҒ„гҖӮ

гҒқгӮҢгҒ§гҒҜгғ¬гғғгғ„пјҒ

гҖҗз”ұжқҘгҖ‘

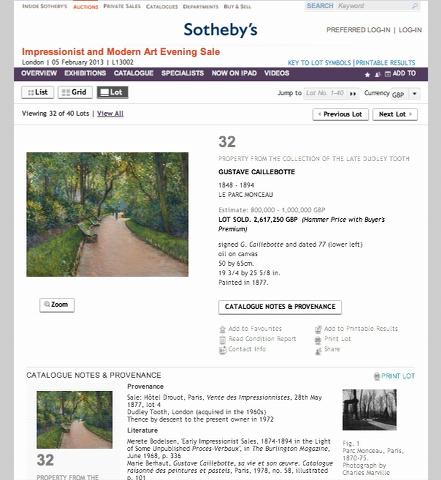

гғ‘гғӘгҖҒгӮӘгғҶгғ«гғ»гғҮгғҘгғ«гӮӘгҒ®1877е№ҙ5жңҲ28ж—ҘгҒ®еҚ°иұЎжҙҫдҪңе“ҒеЈІеҚҙгҒ«гҒҰгҖӮгғӯгғғгғҲгғҠгғігғҗгғј4гҖӮ

гғӯгғігғүгғігҒ®Dudley ToothгҒҢ1960е№ҙд»ЈгҒ«иіје…ҘгҖӮ

1972е№ҙзҸҫеңЁгҒ®жүҖжңүиҖ…гҒ«жёЎгӮӢгҖӮ

иҗҪжңӯдәҲжғідҫЎж јпјҡ?800,000 – ?1,000,000 (7еҚғдёҮеҶҶгҖң1е„„4000дёҮеҶҶ)

иІ©еЈІдҫЎж јпјҡ?2,617,250пјҲ3е„„6еҚғдёҮеҶҶпјү

гҖңдёӯз•ҘпјҲж–ҮзҢ®пјүгҖң

гҖҗдҪңе“ҒгҒ«гҒӨгҒ„гҒҰгҖ‘

гҒ“гҒ®дҪңе“ҒгҒҜгҖҒгғҹгғӯгғЎгғӢгғ«йҖҡгӮҠгҒ®гӮ«гӮӨгғҰгғңгғғгғҲгҒ®е®¶гҒ«гҒ»гҒ©иҝ‘гҒ„гҖҒгғ‘гғӘ8еҢәгҒ«гҒӮгӮӢгғўгғігӮҪгғје…¬ең’(еӣі2)гӮ’жҸҸгҒ„гҒҹгҒЁгҒ•гӮҢгӮӢгҒҹгҒЈгҒҹ2жһҡгҒ®дҪңе“ҒгҒ®гҒҶгҒЎгҒ®1жһҡгҒ гҖӮ

гҒ“гҒЎгӮүгҒ®дҪңе“ҒгҒ§гҒҜгӮ«гӮӨгғҰгғңгғғгғҲгҒҜгҖҒзҹӯгҒҸзҙ ж—©гҒ„зӯҶиҮҙгӮ’дҪҝгҒҶгҒ“гҒЁгҒ§йқ’гҖ…гҒЁгҒ—гҒҹдёӢиҚүгӮ’иЎЁзҸҫгҒ—гҖҒдҪҺжңЁгӮ„гғҷгғігғҒгҒ®е‘ЁгӮҠгҒ®е…үгҒЁеҪұгҒ®еӢ•гҒҚгӮ’з ”з©¶гҒ—гҖҒжҳҺгӮӢгҒ„жҳҘгҒ®ж—ҘгҒ®е…¬ең’гӮ’жҸҸгҒ„гҒҹгҖӮ

гғўгғігӮҪгғје…¬ең’гҒҜгӮӘгғ«гғ¬гӮўгғіе…¬гҒ®е‘Ҫд»ӨгҒ«гӮҲгҒЈгҒҰ18дё–зҙҖеҫҢеҚҠгҒ®иӢұеӣҪеәӯең’гҒ®ж§ҳејҸгҒ§иЁӯиЁҲгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹе…¬ең’гҒ гҖӮ

е…ғгҖ…гҒҜеҖӢдәәгҒ®з§ҒеәӯгҒ гҒЈгҒҹгҒҢгӮӘгӮ№гғһгғіз”·зҲөгҒ®дёӢгҒ®е…¬гҒ®е…¬ең’гҒ«еӨүгӮҸгӮҠгҖҒ1861е№ҙгҒ«еёӮж°‘гҒ«дёҖиҲ¬е…¬й–ӢгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹгҖӮ

гғӯгғігғүгғізҺӢз«ӢзҫҺиЎ“йӨЁгҒ®еӨ§еӣһйЎ§еұ•гҒ«гӮҲгҒЈгҒҰгҖҢйғҪдјҡгҒ®еҚ°иұЎжҙҫгҖҚгҒЁеҗҚд»ҳгҒ‘гӮүгӮҢгҒҹгӮ«гӮӨгғҰгғңгғғгғҲгҒҜгҖҢе…¬ең’гҖҚгҒ«иҮӘ然гҒЁйғҪдјҡгҒёгҒ®ж„ӣеҘҪгӮ’зөҗгҒігҒӨгҒ‘гӮӢгӮҲгҒҶгҒӘзҙ жҷҙгӮүгҒ—гҒ„дё»йЎҢгӮ’иҰӢгҒ„гҒ гҒ—гҒҹгҒ®гҒ гҖӮ

гӮёгғҘгғӘгӮўгғ»гӮөгӮ°гғ¬гӮӨгғҙгӮ№гҒҜгӮ«гӮӨгғҰгғңгғғгғҲгҒЁгғўгғҚ(еӣі3)гҒ®дёЎдҪңе“ҒгҒ«гҒӨгҒ„гҒҰгҒ“гҒ®гӮҲгҒҶгҒ«жӣёгҒ„гҒҰгҒ„гӮӢгҖӮ

гҖҢгӮ«гӮӨгғҰгғңгғғгғҲгҒЁгҒқгҒ®еҸӢдәәгғўгғҚгҒҜеҗҢжҷӮжңҹгҒ«гӮөгғігғ»гғ©гӮ¶гғјгғ«й§…е‘ЁиҫәгӮ’жҸҸгҒҚгҖҒзҷәиЎЁгҒ—гҒҹгҖӮдәҢдәәгҒҜгҖҒ”еёӮж°‘е…¬ең’\\\\”гҒЁгӮҠгӮҸгҒ‘гғўгғігӮҪгғје…¬ең’гҒЁгҒ„гҒҶгӮөгғігғ»гғ©гӮ¶гғјгғ«й§…гҒЁгҒҜгҒҫгҒҹе…ЁгҒҸйҒ•гҒҶзЁ®йЎһгҒ®иҝ‘д»ЈйғҪеёӮйўЁжҷҜгҒёгҒ®й–ўеҝғгӮ’е…ұжңүгҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гӮӢгӮҲгҒҶгҒ«гӮӮиҰӢгҒҲгӮӢгҖӮгҒ“гҒ®е…¬ең’гҒҜгӮ«гӮӨгғҰгғңгғғгғҲгҒҢ1870е№ҙд»ЈгӮ’дё»гҒ«йҒҺгҒ”гҒ—гҒҹ家гҒӢгӮүгҒ»гҒ©иҝ‘гҒҸгҒ«гҒӮгӮҠгҖҒе…ғгҖ…гҒҜ18дё–зҙҖгҒ«з§Ғзҡ„гҒӘдёҖйўЁеӨүгӮҸгҒЈгҒҹеәӯгҒЁгҒ—гҒҰиЁӯиЁҲгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹгӮӮгҒ®гҒ гҖӮгғ•гғ©гғігӮ№йқ©е‘ҪгҒ®й–“гҒ«гҒҜж”ҝеәңгҒ®жүҖжңүзү©гҒ гҒЁе®ЈиЁҖгҒ•гӮҢгҒҹгҒ®гҒ гҒҢгҖҒе…ЁдҪ“зҡ„гҒ«иҚ’е»ғгҒ—дҪҝгӮҸгӮҢгҒӘгҒҸгҒӘгӮҠгҒӘгҒҢгӮүзҙ„10е№ҙй–“еҖӢдәәгҒ®жүҖжңүгҒ§жңүгӮҠз¶ҡгҒ‘гҒҹгҖӮ第дәҢеёқж”ҝгҒ®й–“гҒ«ж”ҝеәңгҒҢгҒқгӮҢгӮ’гҒҚгҒЎгӮ“гҒЁеҸ–гӮҠжҲ»гҒ—дҝ®еҫ©гӮ’гҒ—гҒҰгҖҒгғўгғігӮҪгғје…¬ең’гҒҜ”гғ‘гғӘгҒ®гӮӮгҒЈгҒЁгӮӮйӯ…еҠӣзҡ„гҒӘж•Јжӯ©йҒ“гҒ®гҒІгҒЁгҒӨ”гҒ«гҒӘгҒЈгҒҹгҒ®гҒ§гҒӮгӮӢгҖӮ(J. Sagraves in Gustave Caillebotte: The Unknown Impressionist (exhibition catalogue), op. cit., p. 81)гҖҚ

1870е№ҙд»ЈгӮ’йҖҡгҒ—гҒҰгҖҒгӮ«гӮӨгғҰгғңгғғгғҲгҒЁгғўгғҚгҒҜгҒ—гҒ°гҒ—гҒ°дјјгҒҹгӮҲгҒҶгҒӘдё»йЎҢгҖҒзү№гҒ«гғ‘гғӘгҒЁгҒқгӮҢгӮ’еҸ–гӮҠе·»гҒҸгӮӮгҒ®гӮ’жҸҸгҒ„гҒҹгҖӮ

е®ҹ家гҒҢиЈ•зҰҸгҒ§гҒӮгҒЈгҒҹгӮ«гӮӨгғҰгғңгғғгғҲгҒҜгҒ“гҒ®й–“гғўгғҚгҒ«зөҢжёҲзҡ„жҸҙеҠ©гӮ’гҒ—гҖҒгҒҫгҒҹгҒ„гҒҸгҒӨгҒӢгҒ®гғўгғҚгҒ®дҪңе“ҒгӮ’иіје…ҘгҒ—гҖҒгӮігғ¬гӮҜгӮ·гғ§гғігҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гҒЈгҒҹгҖӮ

гӮёгғҘгғӘгӮўгҒҜгҒ“гҒ®дҪңе“ҒгҒ«гҒӨгҒ„гҒҰгҖҢзӯҶйҒЈгҒ„гӮ„ж§ӢеӣігҒҜгғўгғҚгӮ’жҖқгҒ„иө·гҒ“гҒ•гҒӣгӮӢгҖӮгҒ—гҒӢгҒ—гӮ«гӮӨгғҰгғңгғғгғҲгҒ®жҸҸеҶҷгҒҜгҖҒгғўгғҚгҒҢжҸҸгҒ„гҒҹе…¬ең’гҒ®е…үжҷҜгҒЁгҒ„гҒҶгӮҲгӮҠгӮӮгҖҒеҪ“жҷӮгӮ«гӮӨгғҰгғңгғғгғҲгҒҢжүҖжңүгҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гҒҹ”гӮўгғ‘гғјгғҲгҒ®е®ӨеҶ…(еӣі4)”гҒ«дјјгҒҰгҒ„гӮӢгҖӮдёЎдҪңе“ҒгҒ«гҒҜеәғгҒҸе№іеқҰгҒӘйҖҡи·ҜпјҲе…¬ең’гҒ®жӯ©йҒ“гғ»еәҠпјүгҖҒеүҚйқўгҒёгҒ®жҖҘгҒӘеӮҫж–ңгҖҒдҪңе“ҒгҒ®дёӯеӨ®гҒ®ж–ӯгҒЎиҗҪгҒЁгҒ—гҒҢиҰӢгӮүгӮҢгӮӢгҖӮгҒҫгҒҹдёЎдҪңе“ҒгҒ®йҖҡи·ҜгҒ®зөӮгӮҸгӮҠгҒ«гҒҜеӯӨзӢ¬гҒ§гҖҒеҰҷгҒ«е°ҸгҒ•гҒҸгҖҒгҒјгӮ“гӮ„гӮҠгҒЁгҒ—гҒҹдәәзү©гҒҢжӨҚзү©гҒ«иҰҶгӮҸгӮҢгҖҒгҒ»гҒјеҹӢгӮҒгӮүгӮҢгӮӢгӮҲгҒҶгҒ«з«ӢгҒЈгҒҰгҒ„гӮӢгҖӮгӮ«гӮӨгғҰгғңгғғгғҲгҒҜгҒ“гҒ®гӮҲгҒҶгҒ«гғўгғігӮҪгғје…¬ең’гӮ’жҸҸгҒҸгҒ“гҒЁгҒ§гҖҒ家гҒ®иҝ‘гҒҸгҒ«гҒӮгӮӢе…¬ең’гҒЁеҝ«йҒ©гҒ§гӮӮгҒӮгӮҠдёҚеҗүгҒӘж„ҹгҒҳгҒ§гӮӮгҒӮгӮӢгғ—гғ©гӮӨгғҷгғјгғҲгҒӘеҶ…йқўз©әй–“гӮ’гҒӘгҒһгӮүгҒҲгҒҹгҒ®гҒ гҖӮ (ibid., p. 81)гҖҚгҒЁиҝ°гҒ№гҒҰгҒ„гӮӢгҖӮ

гғ•гӮЎгғғгӮ·гғ§гғҠгғ–гғ«гҒӘиЎЈжңҚгӮ’гҒҫгҒЁгҒЈгҒҹз”·еҘігӮ„еӯҗдҫӣгҒ®гҒ„гӮӢгғўгғігӮҪгғје…¬ең’гҒ®зӨҫдјҡзҡ„гҒӘеҒҙйқўгӮ’жҸҸгҒ„гҒҹ(еӣі3)гғўгғҚгҒЁйҒ•гҒЈгҒҰгҖҒгӮ«гӮӨгғҰгғңгғғгғҲгҒҜз·©гӮ„гҒӢгҒӘгӮ«гғјгғ–гҒ®жӯ©йҒ“гӮ’дёӯеҝғгҒ«зҪ®гҒҚгҒқгҒ®дёҠгҒ«иҰҶгҒҶгӮҲгҒҶгҒ«йқ’гҖ…гҒЁгҒ—гҒҹдёӢиҚүгӮ’жҸҸгҒҸгҒ“гҒЁгҒ§гҖҒж®ҶгҒ©еҶ…йқўгҒ®е№»еҪұгҒ§гҒӮгӮӢгҒӢгҒ®гӮҲгҒҶгҒӘе…¬ең’гҒ®гӮҲгӮҠеӯӨзӢ¬гҒӘйқўгӮ’иЎЁзҸҫгҒ—гҒҹгҖӮ

жӨҚзү©гӮ„жңЁгҖ…гҒҢж…ҺйҮҚгҒ«жҸҸгҒӢгӮҢгҒҰгҒ„гӮӢгҒЁеҗҢжҷӮгҒ«гҖҒгҒ“гҒЎгӮүгҒ«еҗ‘гҒӢгҒЈгҒҰжӯ©гҒ„гҒҰгҒҸгӮӢе°ҸгҒ•гҒӘз”·жҖ§гҒ®дәәеҪұгӮ’ең§еҖ’гҒ—гҖҒж§ӢеӣігӮ’ж”Ҝй…ҚгҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гӮӢгҖӮ

еӨ§гҒ–гҒЈгҒұгҒ§ж•°е°‘гҒӘгҒ„зӯҶгҒ§жҸҸгҒӢгӮҢгҒҰгҒ„гӮӢгҒҢгҖҒз”·жҖ§гҒҜгӮ°гғ¬гғјгҒ®гӮ№гғјгғ„гҒЁеёҪеӯҗгӮ’гҒӢгҒ¶гҒЈгҒҹгғ‘гғӘзҙіеЈ«гҒЁеҲҶгҒӢгӮӢгҖӮ

гҒ•гӮүгҒ«гҖҒжіЁж„Ҹж·ұгҒҸй…ҚзҪ®гҒ•гӮҢгҒҹдҪҺжңЁгӮ„иҠқе°ҸйҒ“гӮ„иҰҸеүҮжӯЈгҒ—гҒҸй…ҚзҪ®гҒ•гӮҢгҒҹгғҷгғігғҒгҒҜгҖҒйғҪеёӮгҒ®йӣ°еӣІж°—гӮ’йҶёгҒ—гҒ гҒ—гҖҒеҗҢжҷӮгҒ«еҠӣеј·гҒҸгғҖгӮӨгғҠгғҹгғғгӮҜгҒӘж§ӢеӣігӮ’дҪңгӮҠеҮәгҒ—гҒҰгҒ„гӮӢгҖӮ

Sale: Hôtel Drouot, Paris, Vente des Impressionnistes, 28th May 1877, lot 4

Dudley Tooth, London (acquired in the 1960s)

Thence by descent to the present owner in 1972

гҖҗLiteratureгҖ‘

Merete Bodelsen, ‘Early Impressionist Sales, 1874-1894 in the Light of Some Unpublished Procès-Verbaux’, in The Burlington Magazine, June 1968, p. 336

Marie Berhaut, Gustave Caillebotte, sa vie et son œuvre. Catalogue raisonné des peintures et pastels, Paris, 1978, no. 58, illustrated p. 101

Pierre Wittmer, Caillebotte au jardin. La Période d’Yerres (1860-1879), Saint-Rémy-en-l’Eau, 1990, p. 242

Marie Berhaut, Gustave Caillebotte. Catalogue raisonné des peintures et pastels, Paris, 1994, no. 64, illustrated p. 97

Gustave Caillebotte: The Unknown Impressionist (exhibition catalogue), Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris; The Art Institute of Chicago & Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, 1994-95, illustrated p. 151 (in Paris); p. 81 (in Chicago)

гҖҗCatalogue NoteгҖ‘

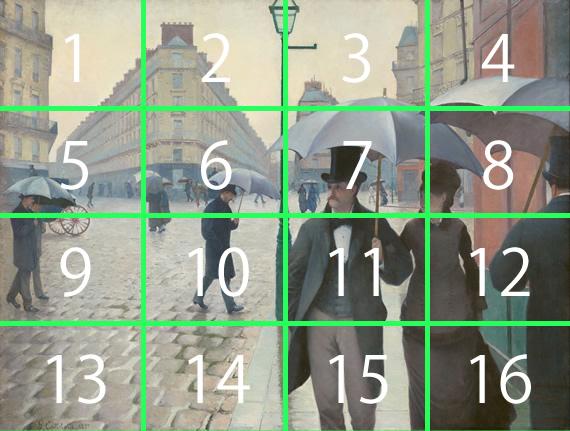

The present work is one of only two known paintings that Caillebotte executed on the subject of Parc Monceau (fig. 2), a public garden located near the artistвҖҷs home on rue de Miromesnil, in the eighth arrondissement of Paris. In the present version, Caillebotte has depicted the park on a bright spring day, using short, quick brushstrokes to render its lush undergrowth and to explore the play of light and shadow on the shrubs and around the benches. Commissioned by the Duke of Orléans, Parc Monceau was designed in the style of the English garden in the second half of the eighteenth century. Originally a private garden, it was converted into a public park under Baron Haussmann, and opened to the public in 1861. Caillebotte, labelled by a major retrospective exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London as the вҖҳurban ImpressionistвҖҷ, found in the park a great subject to paint, as it combined his love of nature with that of the city.

Julia Sagraves wrote about this subject-matter in the work of both Caillebotte and Monet (fig. 3): вҖҳAt the same time that they were painting and exhibiting pictures of the area around Gare Saint-Lazare, Caillebotte and his friend Monet appear also to have shared an interest in another very different kind of urban space: the public city garden, and, in particular, Parc Monceau. The park was located only blocks away from where Caillebotte lived throughout most of the 1870s. It was originally laid out in the eighteenth century as a private, picturesque garden. During the French Revolution, it was declared the property of the State, but in the ensuing decades it continued to pass in and out of private ownership, while also falling into general disrepair and disuse. It was only during the Second Empire, when the State firmly reclaimed and restored it, that Parc Monceau became вҖңone of the most agreeable promenades in ParisвҖқ’ (J. Sagraves in Gustave Caillebotte: The Unknown Impressionist (exhibition catalogue), op. cit., p. 81).

Throughout the 1870s, Caillebotte and Monet often chose to paint similar subjects, particularly views of Paris and its environs. Caillebotte, whose family belonged to the affluent grande bourgeoisie, also provided financial support to Monet during this time, and acquired several of MonetвҖҷs paintings for his collection. Writing about the present work, Julia Sagraves observed that it вҖҳrecalls Monet in both its brushwork and composition. However, CaillebotteвҖҷs image resembles not so much MonetвҖҷs own views of the park, but instead his Apartment Interior [fig. 4], which Caillebotte owned at the time. In both works, a wide, smooth passageway (garden path, floor), tipped dramatically forward, cuts through the centre of the picture. At the end of this corridor stands a solitary, strangely diminished, indistinct figure, encased and nearly overwhelmed by the surrounding plant life. In depicting Parc Monceau in this manner, Caillebotte likened the space of his neighbourhood garden to private interior space, at once comforting and menacingвҖҷ (ibid., p. 81).

Unlike Monet, whose depictions of the Parc Monceau focused on its social aspect, with groups of fashionably dressed men, women and children (fig. 3), Caillebotte chose to represent a more solitary vision of the park, centred around the gently curving line of the path, and the lush greenery that closes above it, almost creating the illusion of an interior space. While the plants and trees appear to be carefully designed, their wild growth dominates the composition, towering over the small figure of a man who walks down the path towards the viewer. Although executed in a few sketchy brushstrokes, the man, wearing a grey suit and a hat, can be identified as a Parisian gentleman. Furthermore, the meticulously aligned shrubs and grass alleys and the rhythmically spaced benches give the scene its air of urban environment, while at the same time creating a vibrant, dynamic composition.

пјҲquoted from Sotheby’sпјү

Comment

No comments yet.